In the aftermath of the ground-breaking exhibition of modernism from Ukraine ‘In the Eye of the Storm’, its co-curator Katia Denysova reflects on justice in the realm of art history. Erased by Russian colonialism for centuries, the place of Ukraine’s artists and heritage in global cultural history must be restored.

‘What is characteristically Ukrainian about these artworks?’ Journalists regularly ask me this question when viewing the exhibition ‘In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s’, which has been touring Europe for the last two years. Its core is composed of pieces from the collections of the National Art Museum of Ukraine and the Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema of Ukraine, shipped out of the country in November 2022 amidst heavy Russian bombardment. Some of my interlocutors venture further by enquiring how the displayed art differs from that of ‘Russia’. The fact that these artworks were created in Ukraine by artists living on its vast territory and were often informed by a particular local context and indigenous pictorial traditions fails to make them sufficiently ‘Ukrainian’ for Western observers. In response, I sometimes ask, ‘What is characteristically French about Henri Matisse’s paintings?’ or ‘How does art produced by Scottish artists differ from that of their English counterparts?’ Unsurprisingly, nobody dignifies such questions with answers, recognising their irrelevance and inappropriateness. There are some questions, however, that I do want answered. How did it happen that the art of Ukraine became absent from the annals of art history, and the country’s culture turned into a blindspot? And why did it take the Russian Federation’s brutal and unprovoked full-scale invasion of Ukraine and genocidal killing of its population for this blindspot to be finally acknowledged?

Art is a powerful tool in shaping cultural narratives and defining identities. The regimes in the Kremlin, past and present, have been acutely aware of the value of cultural diplomacy. For centuries, they invested heavily in cultivating the idea of ‘great Russian culture’. The construction of this image came at the expense of other nations, long subjugated and overshadowed by multiple guises of the Russian empire. Advancing its expansionist, imperial project, the so-called ‘older, Russian brother’ appropriated the cultural and historical heritage of overpowered nationalities. The art and artists they could not conveniently claim as ‘Russian’ were either disparaged or ruthlessly purged.

International cultural institutions have for far too long overlooked this history of Russian imperialism and colonialism. In 1934–35, the Pennsylvania Museum of Art, in cooperation with the American Russian Institute for Cultural Relations with the Soviet Union, staged the exhibition ‘The Art of Soviet Russia’. The foreword in the accompanying catalogue, written by the Pennsylvania Museum’s director, Fiske Kimball, stated: ‘Among the primal artistic forces of the modern world has been the genius of the Russian people’ (my emphasis). The introductory essay by Christian Brinton, one of the first collectors of ‘Russian art’ in the US, proceeded to discuss this ‘genius’ referring to it interchangeably as that of ‘Soviet Russia’, ‘Soviet Union’ and ‘Russia’, on occasion even resorting to ‘Slavic’. Yet, among the eighty or so showcased artists were representatives from the non-Russian republics of the USSR, including those active in Tbilisi, Yerevan, Tashkent, and Kharkiv. Artists from Kharkiv, which had been the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic before its move to Kyiv in June 1934, were the most numerous, and included Vasyl Sedliar (1899–1937) and Sofiia Nalepynska-Boichuk (1884–1937, Polish: Zofia Nalepińska), members of the leading artistic group of Soviet Ukraine known as boichukisty (the Boichukists), named so after their leader Mykhailo Boichuk (1882–1937).

During the decade before the Pennsylvania exhibition, the Boichukists gained acclaim across the Soviet Union as artists-monumentalists, completing state commissions for public art. In their murals, the group aimed to find a visual idiom that would be intelligible to the predominantly peasant Ukrainian masses and derived from their native creative traditions. This quest resulted in a fascinating, idiosyncratic fusing of Byzantine iconography, Ukrainian folk art, and some of the latest achievements of European modernism with Soviet content. The Boichukists’ dual focus on socialist values and the national agenda aligned with the broader cultural politics in early Soviet Ukraine, whose intelligentsia emphasised the national dimension of the emerging communist culture. In the 1920s, artists and writers embarked on an autonomous cultural trajectory yet unimpeded by the dictates of the Soviet centre. These separationist artistic currents developed as a legacy of statehood, which Ukrainians had attained in the aftermath of the Russian Empire’s collapse, proclaiming the independent Ukrainian People’s Republic in early 1918. For the first time in centuries, Ukrainians defined themselves as a modern polity, ending the imperial subjugation of their culture, and using art to assert their distinct, self-sufficient identity. Even though the national Ukrainian forces eventually lost to the Bolsheviks, for Ukrainian intellectuals who had experienced this period of sovereignty, however short, there was no turning back: their national demands had to be recognised by the Soviet authorities.

And so they were. In 1928 and 1930, for example, Ukraine had a separate section within the Soviet pavilion at the Venice Biennale, with the Boichukists featuring prominently among the represented artists. But by the end of the 1930s, the space for such explorations of national culture in the USSR had all but disappeared. The subsequent branding of artists from various republics as those of Soviet Russia reflected a profound shift in the Bolsheviks’ attitude to the national question. Underpinned by Stalin’s centralisation drive, the new rhetoric recovered the old imperial myth about the greatness of the Russian people. They were favoured at the expense of all other nationalities, with Russification portrayed as an enlightenment mission. Three years after the exhibition in Pennsylvania, leading members of the Boichukists, including Boichuk, Nalepynska-Boichuk and Sedliar, were executed as ‘Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists’; a fate that befell hundreds of Ukrainian-Soviet cultural practitioners. In the wake of their purging, the Soviet regime systematically destroyed all public art created by the Boichukists.

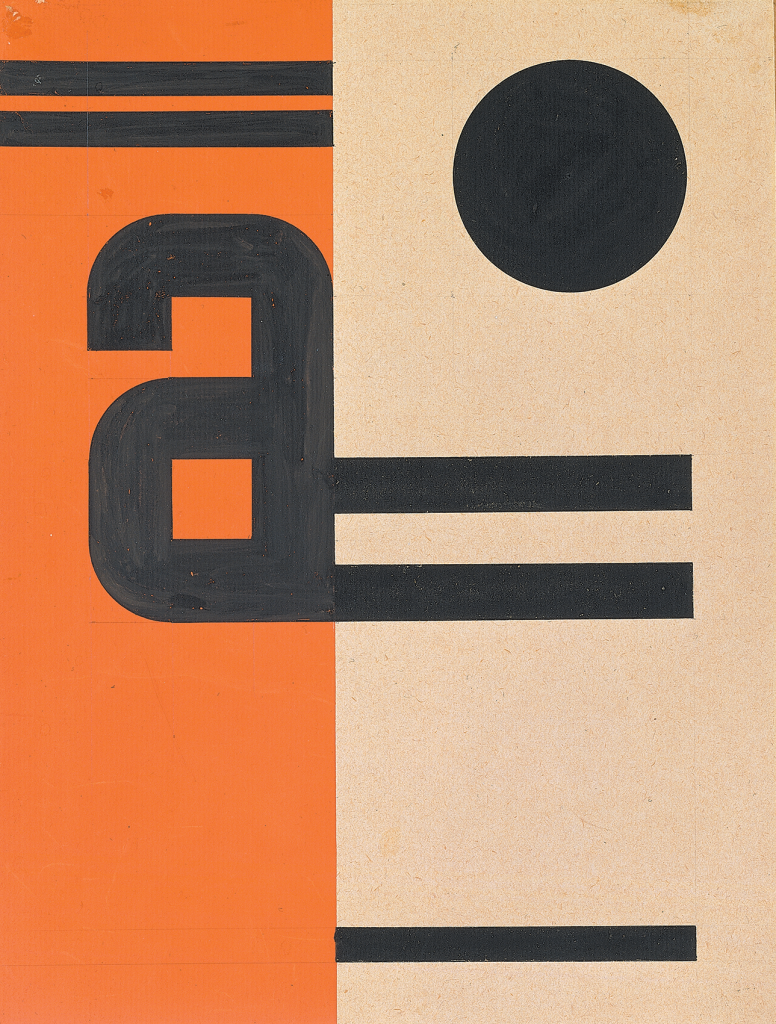

The Pennsylvania exhibition is one of the first examples of presenting the cultural achievements of the Soviet Union — a multinational empire covering the expanse between the Pacific Ocean and the Black Sea, with eleven time zones and an ethnically and linguistically diverse population of almost 300 million people at its peak — as those of ‘Russia’ and ‘Russian people’. This misleading simplification led to the appearance of the term ‘Russian avant-garde’. An umbrella definition, it encompasses art produced in the final decades of the Russian Empire and early years of the Soviet Union, incorporating diverse personalities who were not always ‘Russian’ nor came from the Russian heartland. The list includes, among others, Alexandra Exter (1882–1949, Ukrainian: Oleksandra Ekster), who was born in the Polish town of Białystok, then under the Russian Empire, to a Greek mother and a Belarusian-Jewish father, grew up in Kyiv, spent considerable time in Paris and oversaw the artistic direction of the embroidery workshop in the Ukrainian village of Verbivka; in 1924, she defected from the Soviet Union, settling in France for the rest of her life. Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935, Polish: Kazimierz Malewicz, Ukrainian: Kazymyr Malevych), an ethnic Pole born in Kyiv, who grew up in the Ukrainian countryside, developed as an artist in Moscow and worked in the Russian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian republics of the USSR. And Vasyl Yermilov (1894–1968), an artist from Kharkiv, who spent most of his life in his hometown. It appears at least short-sighted, if not outright preposterous, to band these and many other artists together under any mono-ethnic identifier, let alone the Russian one. Since the 1960s, however, a significant body of research has emerged in Western scholarship, viewing the artistic production of the late Russian Empire and the early Soviet Union under precisely such a narrow classification.

Vasyl Yermilov, Cover Design for Journal Avanhard, 1929, ink and gouache on paper, 30.5 × 22.9 cm, National Art Museum of Ukraine

We can trace this oversight to the 1962 monograph The Great Experiment: Russian Art 1863–1922 by the British researcher Camilla Gray, the first English-language scholarly publication dedicated to the art produced in the final decades of the Russian Empire and early years of the Soviet Union. Gray was the first Western scholar to gain access to the hitherto locked-away archives of Moscow and Leningrad long before her counterparts in the USSR could study these materials. But the author did not only examine the art of the Russian heartland, with her text containing ample references to events, institutions and practitioners in Kyiv, Odesa and Vitsebsk. Ukraine and Belarus, however, are never mentioned; instead, everything is presented as happening ‘in Russia’ or described as ‘Russian’. Gray, therefore, set a dangerous precedent in art history of conflating the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union and casting both as nebulous ‘Russia’. The book’s 1963 German-language translation titled Die russische Avantgarde der modernen Kunst 1863–1922 launched the term ‘Russian avant-garde’ into broad circulation. Consequently, it became an integral part of the Western canon of modernism and a profitable art market category.

After the collapse of the USSR, the routine use of ‘Russia’ as shorthand for the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union was extended to incorporate the contemporary Russian Federation. By the same logic, Russians became the only legitimate heirs to the vast cultural heritage of these multinational empires. But if succumbing to Russian imperial and Soviet propaganda before the fall of the Soviet Union might be forgivable, the complete absence of a post-imperial acknowledgement in the twenty-first century is baffling. In many respects, this is symptomatic of the persistent reluctance to recognise various iterations of the Russian state as colonisers. It also stems from the Western fascination with ‘great Russian culture’ and excessive romanticising of the ‘mysterious Russian soul’. As a result, international academia and institutions became culprits in perpetuating the imperial rhetoric with its systematic erasure of agency and the value of non-Russian cultures.

Such an unreflective and uncritical attitude towards ‘Russia’ was on global display in 2017 when the world’s leading museums staged exhibitions to celebrate the centenary of the ‘Russian Revolution’. By that point, the Russian Federation had already annexed Crimea, violating Ukraine’s internationally recognised borders, and started the proxy war in the country’s Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Yet the discourses of academic art history and art institutions continued as before. With such titles as ‘Red Star Over Russia’ (Tate Modern), ‘A Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde’ (Museum of Modern Art) and ‘Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932’ (The Royal Academy of Arts), the 2017 shows propagated the homogenising Russo-centric interpretations of art history in the so-called ‘post-Soviet space’.

In this context, to think that culture and art are outside politics appears, at best, naïve and careless. And the effects of this negligence are far-reaching. I currently teach a course on modern art of eastern Europe at a German university, focusing specifically on Ukraine. When I asked students to describe familiar art from the region, many referenced El Lissitzky’s poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919) and Malevich’s abstract canvases. But very few knew about the former’s Jewish and the latter’s Polish-Ukrainian heritage; to my students, these artists were simply ‘Russian’. Unsurprisingly, no one in the class had previously heard about the Boichukists.

To return to the questions I posed at the start of this essay: Ukraine had disappeared from the annals of art history because the Russian imperial regimes killed our artists, destroyed our artworks, erased their names from official records, and appropriated what remained. A toolkit they applied with many other nations. The dispensation of justice for Ukraine, therefore, does not only mean restoring our internationally recognised borders, prosecuting the Russian leadership and military for their war crimes, and the Russian Federation’s paying for the damage and ruination it caused Ukraine. Justice also means reclaiming names, institutions and events for Ukraine’s history and cultural heritage. We can achieve such justice only by systematically reassessing the existing art historical canon, exposing and redressing institutional biases, and engendering long-term epistemic reparations. I hope that this long-overdue revisionism can be inclusive, leaving space to embrace and celebrate the multiethnic, multicultural, and multilingual milieus within which the artists from Ukraine had operated. After all, this too, is justice.

Katia Denysova is an art historian and curator, specialising in Ukraine’s modern art. She completed her PhD at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London in 2024, and is currently a research fellow at the University of Tübingen in Germany. Katia is the co-curator of the travelling exhibition ‘In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine’ (winner of the 2023 Apollo Exhibition of the Year Award for the exhibition at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid), and the co-editor of the accompanying catalogue (Thames & Hudson, 2022).

Visual: Anna Zvyagintseva, Kyiv, 2024